Henry Conwell (c. 1748 – April 22, 1842) was an Ardtrea-born Catholic bishop in the United States. He became a priest in 1776 and served in that religious capacity in Ireland for more than four decades. It was after the Pope declined to appoint him Archbishop of Armagh, the diocese in which he served as Vicar General, that he was instead installed as the second Bishop of Philadelphia in 1819, bringing with him to the USA, a young priest named Keenan who was a pastor based at Lancaster.

It was in Philadelphia that Bishop Conwell’s problems really began. A dispute arose between him and the laymen trustees of the diocese of Philadelphia. The new bishop had revoked the faculties (authority) of Rev William Hogan, a favourite of the Board of Trustees for Philadelphia. Conwell then reappointed, as vicar-general of the diocese, a Rev. William Vincent Harold, who had been dismissed by Conwell’s predecessor. Instead of helping matters, the appointment served to further exacerbate the dispute. The Rev. Harold and his bishop soon disagreed on a number of matters and the vicar-general was suspended.

Eventually, Bishop Conwell made his most serious mistake when, on 9th October 1826, he granted the Trustees greater authority in determining salaries and vetoing his appointments. This relinquishing of episcopal rights upset the Holy See and resulted in Bishop Conwell being summoned to Rome. There appeared to be serious dissatisfaction at how the Ardtrea Bishop was dealing with the inherited trustee issues that he faced. It was thought by some that he was neither discrete enough, nor firm enough, in confronting his adversaries, in contrast to his peers who, whilst encountering the same type of issues, were a great deal more diplomatic and dogmatic in their approach. At this time, Bishop Conwell was 78 years of age, and perhaps less inclined to wish to fight with the laymen. It should also be noted that the diocese of Philadelphia was previously known for having such major problems with the Board of Trustees, with two other priests refusing the papal bulls that would have made them bishops, as they would not take on the role of diocesan prelates for that belligerent diocese. Henry Conwell had apparently inherited something of a poison chalice.

Bishop Conwell wanted firmer “regulations” put in place to avoid what he viewed as “foreign interference in the affairs of the church in this country (USA)” within the nomination process for trustees. We can speculate that the “foreign interference” referred to was the Vatican, and more specifically the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda. Conwell appeared to take issue with instruction for nominees being issued from that quarter. It’s possible that he resented a diminishing of the bishopric authority, or independence, in this respect, as well as having to deal with overly-ambitious laymen in the Board of Trustees.

Bishop Conwell had written strongly requesting a diocesan Council be convened to settle the matter, but was called to Rome first to answer questions regarding the problems. When Bishop Conwell set sail for Europe, on 15th July 1828, the organisation of the diocese in Philadelphia fell into decline with no authority to oversee religious life. We have no information as to the exact nature of the discussions that then took place at the Vatican over Conwell’s complaints. We do know that the headstrong bishop from The Loup left Rome without permission and at the risk of losing his diocesan authority. He said mass at the Irish College in Paris, on 15th August 1828. He then left the city in September with interested parties believing that he had returned to Rome. However, the wayward Irishman arrived in New York on 1st October of the year.

It was on 16th August, 1828, that Pope Leo XII agreed to permit a Council of Bishops in the USA. Bishop Conwell was in France when he got the news and made the decision to immediately make his way back to north America. We can only guess at why Conwell was called to Rome just as a Council was being coincidentally convened in his planned absence. It didn’t work, however, and rather than go to his diocese of Philadelphia upon his arrival in the USA, Conwell went straight to Baltimore, the location of the Council which was being held on 4th October. The timing was tight, so we can imagine the determination that Bishop Conwell showed in making the meeting date.

It was to no avail. When Bishop Conwell arrived at the Council – a bishop attending a council of bishops – he was blocked from entry. Archbishop Whitfield had decided that the Rev. William Matthews, then Vicar Apostolic for Philadelphia, would be the representative for that diocese. It is unknown if Whitfield made his decision based upon his belief that Conwell was supposed to be in Rome as ordered by the Vatican, or whether he received specific instructions from Rome to exclude Conwell from proceedings. Whatever the cause, Bishop Henry Conwell faced the ignominy of being banned from attending a Council which he had for some years been trying to have convened. Oh, the murky waters of church politics- Borgias, anyone?

“The Archbishop not only hindered me from occupying my seat among my colleagues and to use a vote of this Province, but even dared to suspend me from celebrating the Sacrifice of the Mass in Baltimore on Sunday in the presence of all the bishops and congregations, as though I were a criminal and he the supreme pontiff.” – Bishop Henry Conwell

It’s fair to say that relations between Conwell and Whitfield were not the warmest – probably closely resembling that between Father Ted Crilly and Bishop Brennan. We can only speculate at the intense desire that Henry Conwell, from The Loup, might have had in wishing to kick Archbishop Whitfield up the arse. After his rejection in Baltimore, Conwell returned to Philadelphia to take up matters again with the trustees.

In April 1828, during Conwell’s sojourn in Europe, elections for the trustees of the diocese of Philadelphia were held. The following were elected as laymen; Archibald Randall, Jon Keefe, Joseph Snyder, John T. Sullivan, Bernard Gallagher, John McGrath, William McGlinchey and Edward Kelley. Bishop Conwell and Rev. Jeremiah Kiely were returned as the clerical members. The domination of Irish names among the trustees gives us some idea of the size and influence of the Irish community in Philadelphia at that time.

Relations between Conwell and the other trustees did not improve over the next two years. It was recognised that the laymen trustees were asserting authority that was not strictly theirs to take. It was said that in the years of 1828 and 1829, the Diocese of Philadelphia “was really in a deplorable condition,” and without the services of a bishop. Henry Conwell was said to have “lived quietly and wrote to Rome by every packet. No oils consecrated for two years, no one to attend to anything, except at the risk of being considered officious.”

It seems that when he was in Rome, Bishop Conwell was informed that should he return to Philadelphia he would be stripped of his faculties (authority within the church). The errant bishop adhered to this edict, and refrained from engaging in the episcopal activities usually required of his position. He wrote to Rome seeking a resolution which arrived on 7th July 1830 when Bishop Kenrick took up a position in Philadelphia. The new bishop coadjutor was given authority over his episcopal superior, Bishop Conwell, and some form of new authority was restored. Strangely, it was at the Council in Baltimore that Father Kenrick was proposed for the new role. Bishop Conwell subsequently supported the proposal, and Father Kenrick was appointed Bishop on 31st March 1830.

The following is from a letter sent by the Archbishop of Baltimore to Bishop England;

“I am requested by the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda to inform you, and all the bishops of the Province, that His Holiness has restored to his grave and favour, the Bishop of Philadelphia, and forgiven his act, done last year minus consideration. I have received and forwarded the briefs for Dr Kenrick, appointed Dr Conwell’s coadjutor, and Administrator of the Diocese of Philadelphia.

“That the honor, dignity and reputation of Dr Conwell are consulted – the administration carried on as if it were spontaneously given by Dr Conwell, who may solemnly officiate, give confirmation in public and private, confer Orders on those whom Dr Kenrick shall approve.”

It’s unusual that a bishop coadjutor be given such authority over a diocesan bishop, given that the role is that of an assistant. The coadjutor is the natural successor to the diocesan bishop upon retirement or death. In this case, it seems that Henry Conwell, who was still formerly diocesan bishop, was content to take a back seat within the running of his diocese, as his “assistant” dealt with the trustees and other administrative matters. It was an arrangement of convenience no doubt designed to avoid further embarrassment to an already beleaguered church Province. Let’s remember that the Catholic Church was not a dominant force with the USA, and was still then trying to firmly establish itself as such. Anti-Catholic sentiment was still rife within the Establishment there, an unfortunate mindset that continued for another 150 years. The Ku Klux Klan, a bastion of white, Protestant authority in many areas was avidly and violently anti-Catholic.

The Sacred Congregation of Propaganda, mentioned, is an influential department within the Catholic Church hierarchy that has responsibility for the spread of global Catholicism, and for the regulation of ecclesiastical affairs in non-Catholic countries, such as the United States of America. Such is the importance of this department’s duties, and the extent of its authority, that the cardinal Prefect of Propaganda is known as the “red pope.” It was primarily this department that dealt with the Bishop Conwell case.

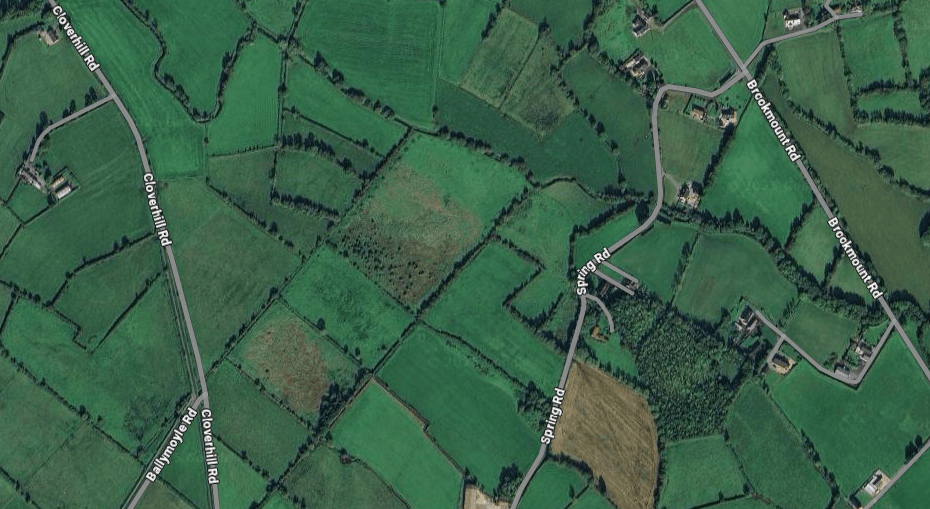

An interesting aside is the fact that Henry Conwell sent to Ireland for his eldest niece Nancy Conwell, daughter of Pat, 1761-1827, who lived in Ballyriff, to accompany him to his new diocese. It was written of Bishop Conwell that, “his was a numerous family, and as long as he lived he had plenty, perhaps too many, nephews and nieces disporting themselves about the Episcopal mansion.”

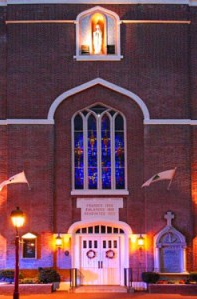

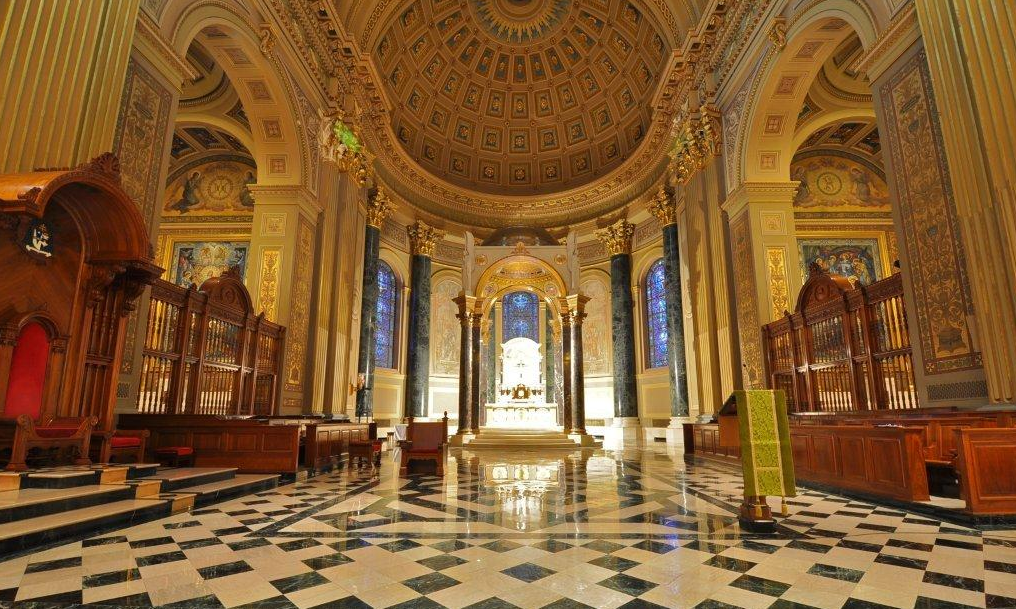

Nancy soon married a Mr Nicholas Donnelly, a well regarded teacher of the classics who taught Latin and Greek to many who went on to take holy orders. Donnelly was said to have suffered for his desire to help those less well-off. He was persecuted and imprisoned for his good works, becoming a close friend of his bishopric uncle-in-law. When Bishop Conwell died, he was initially interred at the humble St Joseph’s cemetery in Philadelphia, before his remains were transferred, to be placed within the Cathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul, the mother church of the Diocese of Philadelphia. Nicholas Donnelly, on his deathbed, is said to have requested, “When I am dead, bury me in the sepulchre wherein the man of God is buried: lay my bones beside his bones.” And so it was that the mortal remains of Nicholas Donnelly were interred in the previous resting place of Bishop Henry Conwell.

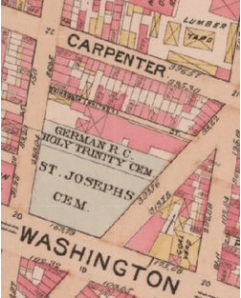

When Bishop Conwell died, he was first interred in St Joseph’s Cemetery, Philadelphia. The map shown is from 1895. The site was also known as Bishop’s Burial Ground. It was opened in 1824 and the title for the burial ground was held in Bishop Conwell’s name, hence its alternative appellation. It necessitated a legal battle upon his death. The cemetery closed in August 1893 and was sold in 1905. All bodies were eventually transferred to Holy Cross graveyard. The Philadelphia newspapers carried this story in June and July of 1905, requesting that relatives of those buried in Bishop’s Burial Ground claim the remains of they would be removed to Holy Cross. We can only wonder where Nicholas Donnelly ended up.

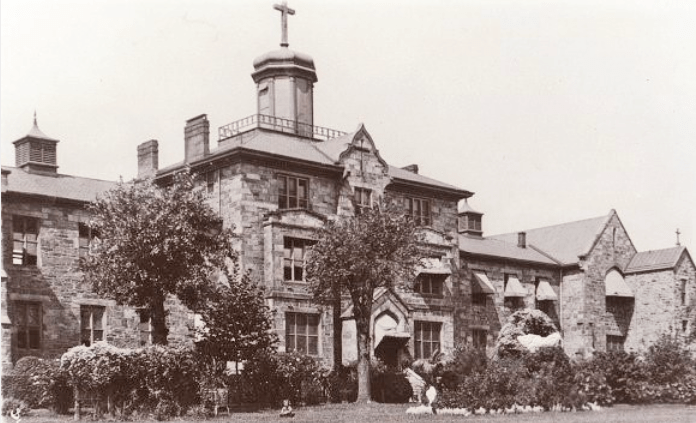

In October 1829, in the Lombard Street home of Mrs Nancy Donnelly, wife of Nicholas, a society was formed for the care of Catholic orphans. It was institutionalised to become St John’s Orphan Asylum. Although only 4 children were cared for initially, the society expanded to care for more than 350 young boys at any given time. The poverty in Philadelphia must have been dreadful to have given rise to such numbers.

St John’s Orphan Asylum, 49th Street and Wyalusing Avenue, Philadelphia. This fine structure and institution emerged from the initial meeting held at the home of Nancy Donnelly (nee Conwell), formerly of Ballyriff, Loup, then of Lombard Street, Philadelphia. The Facebook page for the history of this site can be found here: https://www.facebook.com/st.johnsorphanagephila/

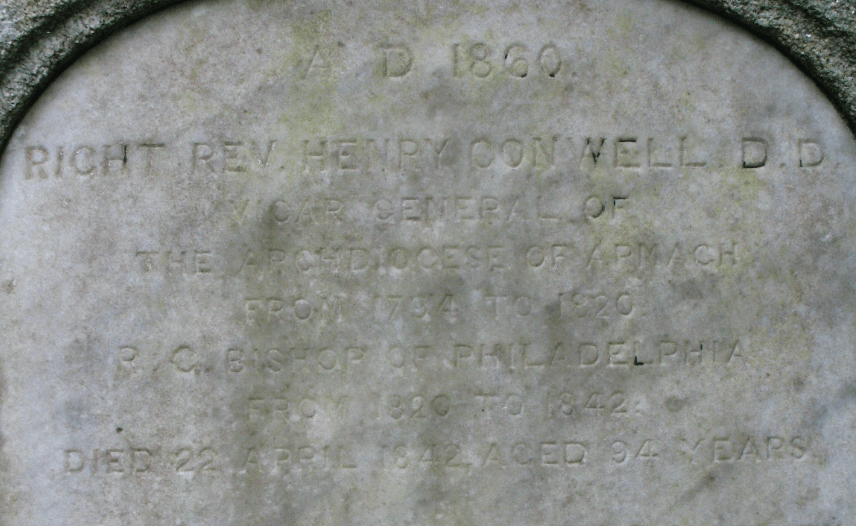

Bishop Henry Conwell lived out his years in Philadelphia in seclusion and prayer, and died there on 22nd April 1842 aged 94. There is no record that he ever returned home to Ireland after his appointment as bishop. He is remembered on the plinth within the Conwell plot – one of a number of notable clerics from that same family with strong connections to the Irish college in Paris. His life was long and of note, given the unfortunate circumstances he found himself in. His legacy seems to be of someone who was fiery in nature, yet who inspired others to do great things. He also appears to have valued his family, with so many of them visiting him in Philadelphia from Ireland. All-in-all, it was a fine life, with achievements, for someone from among the fields of Ardtrea.

Bígí linn

Leave a comment