Ballyeglish Old Graveyard may be small, but it punches well above its weight in terms of the acclaim of those buried there. Although used for more than 1000 years for burials, only a tiny fraction of the grave makers remain, and those are only from burials after 1701. But within those headstones, we find stories that have outlived the centuries that sought to bury them. One of those tales is of a man named Louis Smyth, “A Grand Old Man of Republican Ulster.”

Louis Smyth was born on either 3rd July 1843, or in 1847 (*), the most infamous year of An Gorta Mór (The Great Hunger), when Irish peasantry died in terrible numbers across Ireland from starvation and disease due to the genocidal policies of an apathetic British government at that time. His father was James Smyth, a farmer, and baby Louis entered the world in Ballymulderg Mór, a townland within the Loup portion of the parish of Ardtrea, just 2 miles from the centre of Magherafelt in County Derry. The child was to grow up there, and subsequently dedicate his life’s focus to the causes of Irish freedom, tenant’s rights, and republican beliefs.

(*) Smyth’s marriage and death certificates do not match up in terms of his year of birth, and it’s possible that he either reduced his age upon his marriage to a younger woman, or increased it later in life to receive his state pension earlier. The latter was not unusual for the time, and the records of many people will show such discrepancies in their year of birth for this reason. Such deceptions could also assist the widows and any children of the male deceased.

Ireland, at the time when Louis Smyth was a young man, was a violent and turbulent place. Although the Emancipation Act of 1829 removed many of the sectarian restrictions placed upon Catholics, and the Universities Tests Act of 1871 furthered those human rights, it was not until the Government of Ireland Act of 1920, that anti-Catholic discrimination was officially abolished within Irish society, although partition saw a continuation and expansion of some of those problems under the ruling protestant-Unionist government of the new 6-county state-let. As someone from a strongly Catholic and nationalist background, Smyth saw and experienced firsthand the persecution of those who did not conform to British state edits. As a working class man, he also witnessed the indignities meted out to those of the blue collar persuasion, regardless of creed. Those experiences were to understandably shape his political and social outlook, and his life.

On St Patrick’s Day, 1858, The Irish Republican Brotherhood was founded in Lombard St, Dublin by James Stephens, Tom Clarke Luby, Charlies Kickham and John O’Leary. It was a secretive militant organisation devoted to the overthrow of British rule in Ireland by any means necessary, including violence. The umbrella term “Fenian” came to be applied readily to its members. Louis Smyth was regarded as one of that number.

But support for Republican militancy was not the sum total of Smyth’s efforts to tackle what he saw as injustice and inequality in Ireland. The young man from Ballymulderg was also involved in agitation for land rights for the dispossessed, as well as fighting for progress on the cultural front. He was instrumental in promoting both Gaelic games and language across Ulster, beginning in his home area of south Derry.

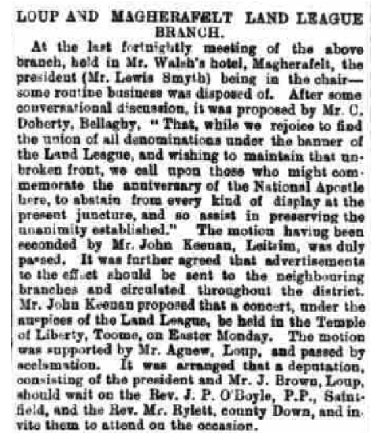

This article is taken from the Derry Journal of Wednesday, March 16th 1881. The Land League was officially set up in October 1879 at the Imperial Hotel, Castlebar, Co. Mayo. It’s aims were to create and protect tenant’s rights, including the right to buy the land they worked. It sought to end landlordism, and attracted support from across the religious divide. One of the first conferences was in Belfast, and was organised by The Route Tenants Defence Association of Ballymoney. Ulster Presbyterians were at the forefront of the fight for tenants’ rights. The Land League of the Loup and Magherafelt was founded on 4th December 1880.

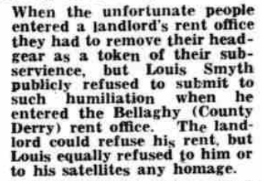

Smyth was a stalwart when it came to the rights of tenants of the land. He is mentioned in William O’Brien’s (politician and social revolutionary) famous “Recollections,” and carried his unshakeable convictions everywhere he went, wielding them against those he felt were guilty of abuse of the people. The adjacent clip is taken from a Derry Journal article of 16th April 1954. It describes Smyth’s approach to landlords.

On 6th December 1881, a Parliamentary election was held in county Derry. A Mr Dempsey, owner of The Ulster Examiner, had been running as an Independent candidate in support of Home Rule. According to a Derry Journal piece of Friday November 25th 1881, Louis Smyth, at this time in his thirties, was again in the thick of it, giving his backing to Dempsey. The Loup man is recorded as having been present at campaign rallies at Inisrush, Gulladuff and Kilrea. Interestingly, he has the letters P.L.G. after his name on each occasion. These initials stood for Poor Law Guardian, an elected position designed to oversee the workhouses in the district. Smyth’s popularity and renown may have been greatly assisted by his involvement in this noble undertaking. The role of P.L.G. is substantial for a man in his thirties. After 1899, the role of Poor Law Guardians was subsumed into that of Rural District Councillor (R.D.C.), an elected position Smyth also held. As for the 1881 election, Mr Dempsey choose to retire from proceedings and so advised his supporters to back Sir Samuel Wilson, a Conservative. Louis Smyth‘s feelings on this development are not recorded.

In April 1887, when Smyth was in his forties, a meeting of Nationalists was held on a Tuesday in the market square, Maghera, to protest against the new Crime Bill. A Mr R.D. Pinkerton of Ballymoney was chairman of proceedings. Notable figures in attendance included 4 Catholic priests, as well as Bernard Rogers, D.C. Gillespie of Coleraine, and Louis Smyth, who “moved a series of resolutions,” all of which received the approval of the assemblage. By this stage in his life Smyth was a person of serious influence. We must presume that his position was gained through much noted activism prior to this event, even if not all was recorded or has yet been discovered.

The words of D.C. Gillespie are of note. He claimed that the Presbyterians were trampled by an intolerant Establishment that used all the influence of men and devils to prevent Presbyterian ministers marrying members of their own church to Episcopalians, and the Salisburys, the Balfours and the Marlboroughs would degrade them again today if they dared… The North would not tolerate coercion in perpetuity, and the orange handkerchief to be forced down their throats with a ramrod. We can see that throughout the nineteenth century, protestant nationalism still had a strong and very public voice across Ireland. It was a status that was sadly to change with the impending decades.

The Irish National League was a political party founded in 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell. It was initially the main support for Parnell’s Irish Parliamentary Party and had, at one time, more than 1000 branches across Ireland. It campaigned for Home Rule, as well as voting and economic reforms. In the longstanding Irish tradition, the National League eventually split, over Parnell’s perceived indiscretions with Kitty O’Shea. (note: the Conwell grave plot is close to that of Louis Smyth‘s final resting place)

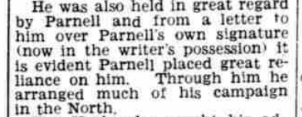

Charles Stewart Parnell was one of the best known Irish politicians of the 19th century. Born into a wealthy landowning family in 1846, he was Fidel Castro without either the beard or the guns. He caused ructions in the British parliament through his sharp wit and high intellect, which he used to confound his adversaries. Parnell’s association with Smyth demonstrates the latter’s high standing in Irish political and social movements.

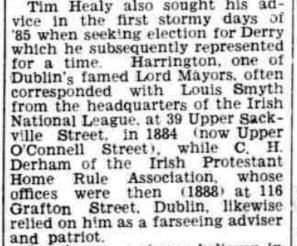

Healy was born in 1855 in Bantry, Co. Cork. His family lost their lands by refusing to renounce their Catholic faith. Initially an acolyte of Parnell, he left after the Kitty O’Shea affair. He was associated with William O’Brien, John Redmond and John Dillon. He was elected MP for South Derry in 1885, losing his seat the following year. Healy was the first Governor-General of The Irish Free State in 1922. Although supportive of Sinn Féin‘s goals, he did not support the physical force movement. As a King’s Counsel, he represented many of those detained after the Easter Rising in 1916.

It was on 29th February 1892 that Louis Smyth, then stated on his marriage certificate as 45 years old, married Mary Agnew of Culbán, Bellaghy, who was at least 20 years his junior, in the presence of Alphonsus Quinn and Brigid Agnew (her sister). Alphonsus, a farmer from Ardboe in County Tyrone, was to marry Mary’s sister, Maggie (Margaret Jane) just 2 years later in the same church. Mary’s father was Henry Agnew, a farmer like her father-in-law. Her mother was Jane Agnew, nee Keenan. The Agnew family had 9 children. In addition to Mary and Brigid, there was also, Henry (John) junior, Isabella (Doherty), Rose, Grace (Scullion), Margaret Jane (Quinn), Thomas and Patrick Joseph (P.J.). The ceremony took place in St. Mary’s Catholic church in Bellaghy. It was a union that saw periods of great adversity, including an uprising in Dublin, a war for independence across Ireland, an Irish civil war, the partition of Ireland, and one world war. Although not to be blessed with children of their own, they remained together through thick and thin until Louis’ death some 33 years later. The Agnew family were to remain active in Irish politics for many decades with Thomas B Agnew, son of Smyth’s brother-in-law, P.J. running for election in 1954 as an abstentionist candidate. P.J. was a former Republican internee at Ballykinlar.

On 11th April 1898, we find Louis Smyth, in his fifties, chairing an “extraordinary” meeting of The Ulster Provincial Council ’98 Centenary Movement. This society was founded to commemorate the centenary of the United Irishmen Rebellion of 1798, a time when Republicanism was first introduced to Ireland by the protestants of the day. Smyth was vice-President of the organisation. The meeting was called to discuss a dispute that had arisen with members of the Howard Street Branch in Belfast, and was held in a “St Mary’s” hall, presumably at the same location on the Falls Road where the teacher training college is today. A number of “Ulster Clubs” were represented and nominations were made. It’s worth noting that, at that time, travel from south Derry to Belfast was no casual thing. Smyth would have taken a considerable period of time to reach the city, although may have had fine company to pass the time with in the person of Mr M. Hurl of Newbridge, who was there representing the Roddy McCorley ’98 Club. The article concluded with the following:

Mr Smyth, in reply, said he thanked the members sincerely for their kindness. He was only doing his duty as an Irishman in presiding at their meeting. He had been born an Irishman, and he hoped he would die in the old faith – (applause) – and in the old political creed of Irish opposition to English misrule. (applause)

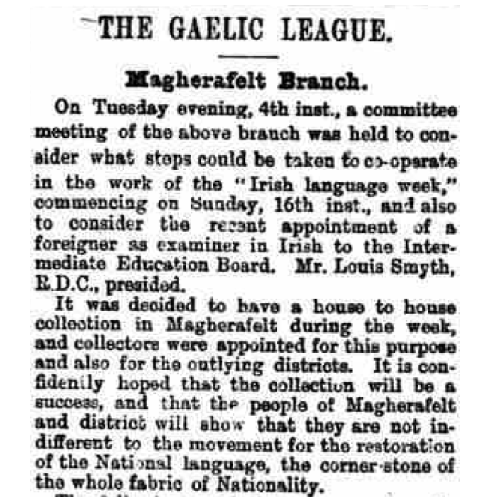

This brief article was taken from the Irish News of Tuesday March 11th, 1902. We can see from this how Louis Smyth, then in his fifties, was to the fore of progressing Gaelic culture in the south Derry area. The Gaelic League, more properly known as Conradh na Gaeilge, was founded in 1893 by Douglas Hyde, a protestant nationalist. It is still going strong today. It seems that the indefatigable Louis Smyth was a member from it’s earliest days. R.D.C. after Smyth’s name refers to Rural District Councillor, an elected position from 1899 on.

In 1905, the Republican political party, Sinn Féin, was founded by Arthur Griffiths. Although initially monarchist and therefore not strictly Republican, it morphed to become a strictly separatist organisation, fighting its first election in North Leitrim in 1908. Louis Smyth was a staunch advocate of the ideals for which Sinn Féin eventually stood, and became a member from the earliest time. As a representative of the Comhairle Ceantair (Area Council) on the Executive Committee, he would have been personally acquainted with Griffiths.

Smyth was also well acquainted with the Belfast Quaker and Republican, Bulmer Hobson who was some decades the Derry man’s junior. Both men were, at some point, members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, with Hobson credited with swearing Padraig Pearse into the secretive group. A complex character, Hobson ran afoul of a number of prominent Republicans over time, particularly during the Easter Rising in 1916 when he was arrested by the rebels. But, in 1903, and still regarded with respect by all, he toured south Derry with Smyth in an attempt to counter British military attempts at recruitment. They held an anti-recruitment rally at Tirkane outside Maghera, with Smyth putting up posters around Magherafelt carrying the same message. The records appear to confirm that many, if not most, of the main political players in Irish politics in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were acquainted with Louis Smyth.

This excerpt, taken from an article in the Derry Journal of 1954, tells us about the arrest of Smyth in 1916. At the time, Smyth was either 69 or 73, no spring chicken for the rigours of the brutal arrest described. It’s interesting to note that some Orangemen came forward to tender bail for the unfortunate Republican. Perhaps this act was due to Smyth’s social activism in defence of tenant’s rights, or his work for the poorhouse, or just in respect of his general disposition. It’s a scenario that one could not envision would occur in later years with anyone other than Smyth. The man from Ballymulderg refused to recognise the court when eventually presented before it and, together with two other south Derry men, namely Hugh Gribben of Anahorish, and Anthony McGurk of Gulladuff, was handcuffed and taken under strong escort to Derry Gaol.

On Monday 2nd May 1916, Smyth and other detainees were assembled in Derry Prison yard where they were handcuffed in pairs and taken to Dublin. Smyth was shackled to Dan Kelly, later of the Irish Customs Service. The men were taken firstly to Trinity College and then to Richmond Barracks, close to Kilmainham Gaol. Smyth was kept there until 12th May, the day on which Seán MacDiarmada and James Connolly (who, because of mortal wounds received in the Rising, was tied to a chair to be shot) were executed by firing squad. The shackled prisoners were then taken to the cattle boat which left from the North Wall in Dublin bound for Holyhead in Wales. They reached landfall at 3am still handcuffed and guarded by a regiment of Sherwood Foresters (who presumably missed the irony of their name given the circumstances). Although the Red Cross was present, it was reported that the soldiers were given refreshments but the weary and sore Irish received only abuse. From Holyhead, the prisoners were moved to Wakefield Prison, West Yorkshire, where Louis languished for 3 weeks. His health was deteriorating rapidly, so his jailers released him fearing he might die in custody. Upon his return to south Derry, Smyth resumed his activism, albeit with some new experiences to report. Smyth campaigned in the 1918 parliamentary election for Louis J Walsh, the same man who taught him Gaelic, on cold winter nights.

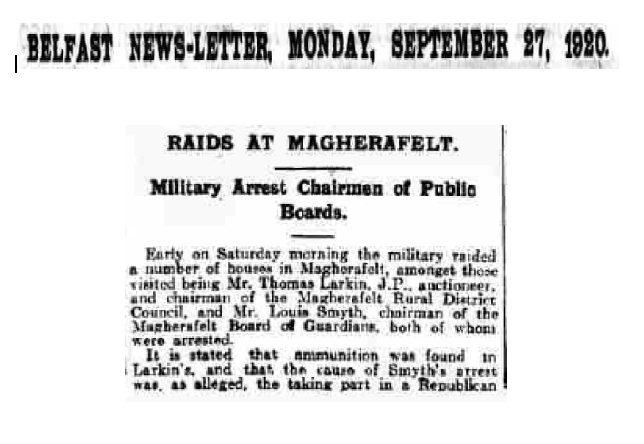

Here we see Smyth again swept up in political developments, this time during the Tan War (War of Independence). He was arrested with a member of another notable Republican family from The Loup, the Larkins. At the time of his arrest, Louis Smyth was either 73 or 77. Whichever figure is true, he suffered arrest four and one half years before his death. Tom Larkin’s brother, Sean, was executed by Free State forces in Drumboe, Donegal 1923.

The Derry Journal in 1954 reported of Smyth that he was instrumental in having the first Gaelic classes started in Magherafelt and sustaining them through many discouraging years…. the proof of his sincerity was seen in the fact that, although then an old man, he sat through many a winter’s night with the boys and girls of his parish and, like them, learned O’Growney… as taught by the tutor, Louis J Walsh. Smyth was also a member of Magherafelt’s first Technical School Committee, set up at the start of the 20th Century.

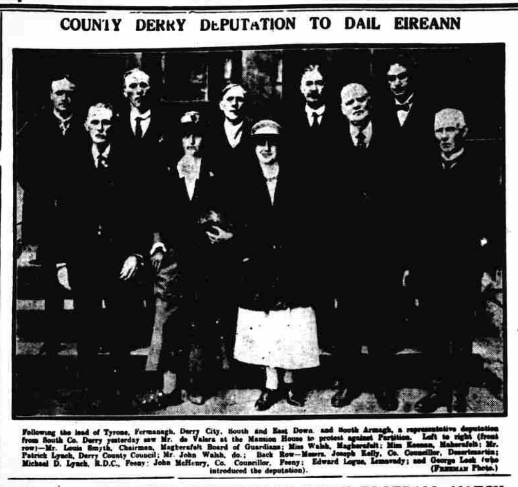

The following photo documents the delegation from County Derry who visited Dublin in September 1921, to register their protest at the partition of Ireland, which was enacted in May of that year. The group met with de Valera, then in opposition to the nascent jurisdictional development. It is worth noting that the delegation choose to meet with the eventual leader of the anti-Treaty side. De Valera was known to be a staunch opponent of the Government of Ireland Act 1920. Nationalists and Republicans, from the six north-eastern counties contained within the new state-let, were understandably distraught at the new political arrangements. We can only imagine how distressed someone like Louis Smyth would have been, to have seen his life’s work of political activism founder upon what was a de facto Orange Order-run state-let, with the subsequent oppression Smyth knew it would bring to his community. We must also consider the possible impact that the many irate delegations from the north would have had upon the decision making of de Valera. Civil War was to break out less than one year after the visit from the Derry delegation, with Republicans from Smyth’s home parish to the fore in fighting the British forces ranged against them, as well as confronting the newly created Free State Army, a proxy force armed and assisted by their former foes in the British Army and Royal Navy. Smyth’s 1921 visit to his nation’s capital, and parliament, took place only a few years before his death.

It was on 4th April 1925, that Louis Smyth died, reputedly at The Bridge Hotel (now known as The Wild Duck) in Portglenone. He owned the establishment, which was close to his wife’s home-place. The cause of death was given as “cerebral embolism.” His devoted wife, Mary, was present by his bedside as Louis finally shook off his mortal coils. On his death certificate, Smyth is listed as a “Retired farmer” (aged 82). It’s a gloriously humble and understated description that does little to truly represent the industrious and influential life of an unassuming hero for the Republicans of Ulster.

Louis Smyth was laid to rest in the family plot at Ballyeglish Old Graveyard. It was reported that both the relatively new Royal Ulster Constabulary, and their assistants in the B-Specials, provided a huge armed guard during the funeral. Perhaps, such unwanted attention from those who represented what Smyth spent his life opposing, was the greatest compliment that they could have given him.

The legacy of Louis Smyth is extensive, but overlooked. Perhaps his humility did not lend itself so well to renown. Yet he was ever present. In each political campaign, each revolutionary movement, each cause of social activism in Ulster and across Ireland, he tossed himself into the fray without serious regard for his welfare. Hopefully, he will eventually be afforded his rightful place among the noble patriots of Ireland who, whether one agrees with them or not, believed strongly enough in their cause to risk all they had.

Bígí linn

Leave a comment