The Derrycloghagh Riot of 1725

“James Johnston, Ballyriff… saw above one hundred persons pursuing the Rev. Mr Thomas Sandys and… saw Mary Mucklehennon of Ballymulligan returning from said pursuit in a very furious manner and… saw a vast number of stones thrown at… and a great number of staves raised against the said Mr Neves and Mr Sandys and their assistants and further saith not”

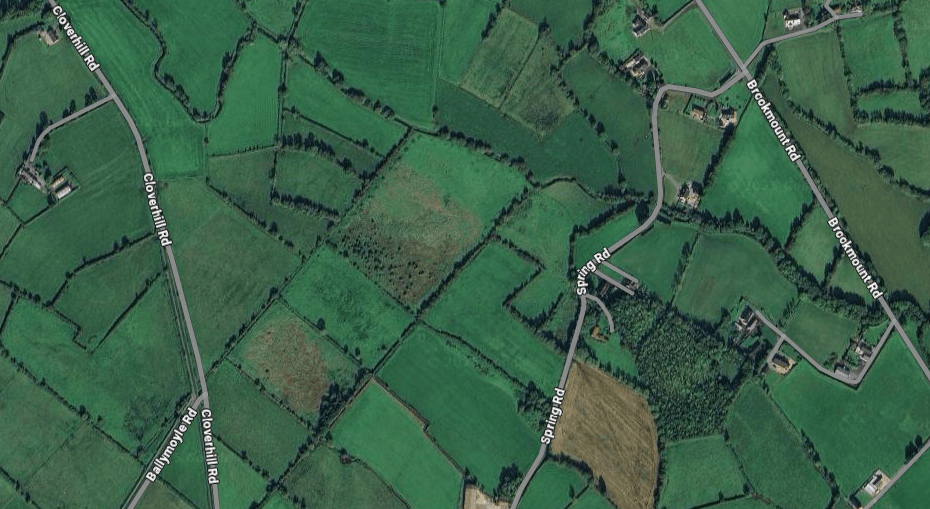

It was on Good Friday, 26th March 1725 (Julian calendar) that an extraordinary event took place in the townland of Ballyneil Beg in the parish of Ardtrea, close to the western shores of Lough Neagh and some 3 miles from Ballyeglish. During a Penal Times mass, which had attracted a crowd of thousands, an attempt was made to arrest one of the keynote speakers. The warrant was presented by the local Anglican curate, Rev Thomas Sandys, who lived close by, along with 8 militia on horseback. The crowd reacted with violence and attacked the arrest party who subsequently escaped bruised and beaten, but alive. The man they tried to arrest remained free.

The incident, of great note at the time, was lost to local folklore until discovered in the 1970’s by a local man, Patrick Larkin, who had been headmaster of a local primary school close to the scene of the trouble. Whilst researching at PRONI, Larkin uncovered correspondence between Rev. Sandys, Thomas Neve (agent for the Irish Society, responsible for the plantation of the area), Rev. William Ussher (Rector of Desertlyn and Lissan; Justice of the Peace), the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (John Carteret), Thomas Marlay (Solicitor General of Ireland) and various other government officials in Dublin. The letters revealed a major incident that had the Dublin authorities worried about the possibility of a national uprising just one generation after the Battle of the Aughrim.

The young man at the centre of the incident went by the name, William Smith, although it was not thought to be his true identity. Little seems to be known about him but it was suggested that he hailed from Limerick. Smith allegedly moved through the countryside addressing those at Penal masses, which were usually held in remote places. His mission appeared to be the fomenting of rebellion against the Anglican state. The official accounts listed “endeavouring to secure an enthusiastic Popish Priest who was preaching sedition” as a primary factor in his arrest.

The Penal Times were harsh throughout, but the earlier years were the worst. In 1725, both Catholics and Presbyterians faced serious discrimination. Catholic services were not banned per se, but all things Catholic were discouraged, and those of that faith were prohibited in the areas of law, property ownership, education, religious buildings, and even keeping good horses. They were also banned from carrying arms. The authorities lived in fear of another uprising by the majority of the Irish population, so any tiny flame of dissent was quickly snuffed out. Derryclogagh was an example of the draconian methods employed.

The name Derryclogagh was lost to the local community until the discovery of the official letters in Belfast. The place-name meaning is subject to debate. Derry refers to an oak wood. Clogagh may have various interpretations; a rounded, bell-shaped hill (P.W. Joyce); a grey stone (Joyce); a stony place (Joyce); a place of round hills (Joyce). Further research is needed to settle upon the most likely meaning.

Reports of attendance at the mass ranged from 2000 to more than 4000 (Neve). It would have been perhaps the largest documented mass in Ireland throughout the entire Penal Times. We can only imagine how delighted priests today would be at the thought of thousands attending their services. The surprising aspect of the event was the attendance of numbers who were not Catholic. It seems that many Presbyterians turned up for the speeches about rebellions. Maybe the followers of Calvin and Knox were partial to a bit of sedition.

From the accounts given, it seems that Rev. Thomas Sandys was either the bravest man in Ireland, or the most arrogant and foolhardy. Upon receiving a warrant for Smith’s arrest from Ussher, he claimed to have rode into the crowd alone and remonstrated with Smith. When he found no cooperation there, he moved quickly to the edge of the assemblage to await Neve, who arrived with just 7 other riders. The militia (approximate to today’s Territorial Army) from nearby Moneymore who had been summoned did not appear, and so the 9 men rode into the multitude to effect Smith’s arrest. It went just about how you would expect.

“Bryan O’Kelly of Ballydonnell… said that it was the worst thing that has happened these many years that the said Kelly… did not cut and smash the Rev Thos. Sandys into bits, and further saith not.”

It beggars belief that such a small party of loyalists would confront a crowd of such numbers, and at a time when that crowd was oppressed in a terrible manner. Yet they did. The congregation had no weapons save their staffs and whatever stones they could find, and they were angry. They were also apparently pretty good shots with the stones. Neve was hit in the face and fell from his horse, but his colleagues circled him until he remounted and fled. Our prior acquaintance, Mary Mucklehennon, seems to be the kind of person you don’t want to fall out with and, together with many others, she pursued the Sandy party for one quarter-mile before the authorities made good their escape.

“Sarah Stewart of Ballyrogly… saw… Roger O’Hagan of Ballymuckederrig… throw 2 great stones at Mr Neve and hit him a violent blow on the shoulders with one of the said stones and further saith not.”

Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, there is no mention of what injuries the members of the congregation sustained from the 9 armed riders tearing into and out from their midst. We must presume that those caught in the path of the horses would have been hurt, perhaps even seriously, yet nothing is recorded. No records were found detailing pilgrims who were slashed with swords or who suffered gunshot wounds, or who perhaps felt the sharp effects of a stray stone thrown. We can also only imagine the terror that any children present at the mass would have felt at the onset of violence, and how that trauma would have shaped their future opinions and actions. The names of many of the “rioters” were given in the accounts, but the records suggest that only two were arrested, at least immediately proceeding events.

Trinity Hull allegedly had his head beaten by Hugh Donnelly’s cudgel. Pat and Philemy Tameny both allegedly struck Sandys. James O’Tamany of Ballygurk was one of those pursuing the good reverend. “Richard McCan near Disartmartin” allegedly boasted about how he “had beaten Abraham Leech who assisted Mr Sandys and Mr Neve.” James Pickerin of Ballyronan swore that he saw Ever O’Neill strike Mr Neve’s horse after its rider fell off. In the chaos, many of those involved were not identified. As to what actions were eventually taken against those who were, we might never know.

“Isabell Jameyson… county of Antrim… heard one John McKee of Rouskey… say that he threw stones at the Rev. Mr. T Sandys and Mr Neve and others and put them to the rout.”

One of the things we can be certain of is that the Rev. Thomas Sandys gained some novel material for his next sermon. In his own account, he claimed that he was “pursued by two or three hundred men with stones and clubs for about a quarter of a mile, all along shouting Kill the Devil, Kill the Devil.” Such insults seem tame by today’s standards. Yet Sandys was not to be outdone. He sent a spy after Smith. The agent, unnamed, returned on Easter Sunday night to report that the reverend’s prey was in Tyrone, some 6 miles from Derrycloghagh. Thomas Neve, no doubt still sore from his beating (which can’t have been too serious after all), and “14 well-armed men” surrounded the house they believed Smith to be in, but he had outfoxed them again.

“Neve, being zealously disposed to bring the said Smith to justice, sent four spies after him.” The intel received on 5th April inspired Neve to take 18 armed men to Charlemont to capture the youthful orator. But fate was not with them on that occasion either. A lookout tipped Smith off and he escaped “over the river Bann” (Charlemont stands on the River Blackwater). The boatmen were all Catholic thereabouts and Neve claimed that they took their boats to the other side forcing the pursuers to take the long way around, allowing Smith time to escape. Sandys had put up a reward of £5 for Smith, whereas Neve had placed a bounty of £10 (approx. £1750 today) upon his “papist” head.

It was on Monday 24th April, some 29 days after the Derryclogagh riot, that the unfortunate Smith was eventually captured at Tullyhogue in Tyrone, whilst attending a visitation by a Popish bishop. Smith was taken to Derry where he was tried on two counts. In the first, he was found guilty of using blasphemous words and expressions.

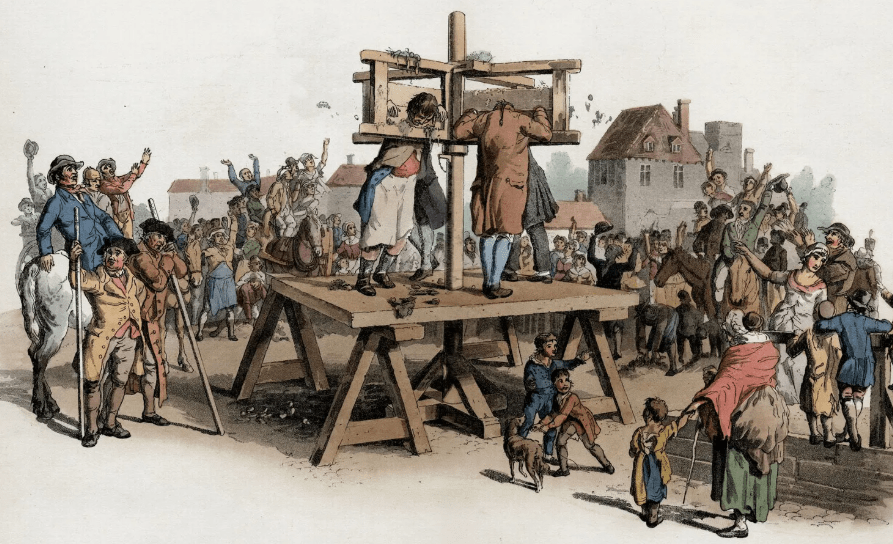

His punishment was to stand at the pillory with his crime “wrote on his breast.” He was then “whipped four times through the streets of the city of Derry” and had the letter “B” burnt onto his face. He was acquitted of the second charge of riot and tumultuous assembly, as well as various counts of assault.

Having been punished for his “crimes” in county Derry, Smith was taken to answer for his transgressions in county Tyrone. He was convicted and received the same punishments there (note: Catholics could not sit on juries or practice law).

The story concludes with William Smith being deemed too dangerous to be left in Ireland and, so, he was forced into exile to “His Majesty’s Plantations in America” under the Banishment Act of 1697 which targeted Catholic clergy. The strangest aspect of this is that Smith was judged to be about 20 years old, much too young to be a priest of any stripe, and was described as a “pretend pilgrim” and “reputed Popish preacher” in the testimonies.

Perhaps the real reason why Smith was so harshly treated was not his religious identity, but his political one. Thomas Sandy had this to say, “… I am concerned the Papists are so uppish and barefacedly insolent, preaching up sedition and blasphemy, making collections, raising money at Mass places, that… the Papists design once more (if they can find an O’Neil to head them) to play over again the same of ‘41” (Rising of 1641 in which Anglicans were expelled from the area).

Thomas Neve expressed similar sentiment when he wrote to The London Society, “The Irish Papists were never so violent since King James the Second’s time as now: they threaten us we hear, to wash their hands in Mr Sandy’s blood and mine etc, and to burn our houses.” Neve believed that four fifths of the local population were then “papists” who, under the influence of “emissaries from Rome” were planning another uprising. History shows that their fears were unfounded then, and it would be 73 years before it was the Presbyterians of Ulster led by a Dublin Anglican who instigated a national rebellion.

Thomas Sandys was replaced as curate of Ardtrea in 1726. He had also held a position in the adjacent parish of Ballinderry and Tamlaght. Thomas Neve was a meteorologist who compiled the earliest known surviving diary of Irish weather which ran from 1711 until 1725, the year of Derryclogagh. He died in 1739, his Ballyneil More farm remaining intact.

John Carteret, aka, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland 1724-1730, aka, 2nd Earl Granville, aka 7th Seigneur of Sark, aka Secretary of State 1742-44, aka Lord Carteret, was a British statesman and Lord President of the Council 1751-63. His family was of Norman descent. John was said to have been the only English noble who spoke fluent German, thus gaining for him a trusted association with George 1, the first king of the Hanoverian dynasty, who spoke little English. It’s an interesting thought that such an esteemed personage as Carteret, known to have had a great fondness for burgundy, would have felt his blood pressure rise considerably due to the actions of locals from the lough-shore region just 5 months into his tenure as Lord Lieutenant.

Carteret was reputed to have held a strong affection for the Irish writer Jonathon Swift, then mired in controversy over his Drapier’s Letters. Carteret inherited a huge one eighth share in the Province of Carolina (later to become North and South Carolina), 60 miles wide and known as The Granville District, which might well have been William’s Smith’s final destination. The Carteret’s lost their land after the US War of Independence. He died in 1763 and was interred at Westminster Abbey. The title of Earl of Granville became extinct in 1776 when John’s son Robert died without issue. Lord John Carteret was portrayed as a villain in the 2011 movie, Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides.

The tricentennial of The Derryclogagh Riot takes place this Good Friday, in a year when both the Julian and Gregorian religious calendars sync to have the holy celebration on the same date. The exact location of the mass place and resultant riot has not yet been found. Nor has anyone located either Mary Mucklehennon’s rosary beads or Hugh Donnelly’s cudgel. The search continues.

Bígí linn

Leave a comment